Genetic polymorphism is very extensive in cross-fertilizing species ( 1, 2), a fact that is reflected in multiple genetic differences between inbred strains. Mammals have sufficient DNA to code for thousands of genes, and significant fractions of samples of loci exhibit polymorphic variation. Thus, unrelated strains of mice differ by hundreds, possibly thousands, of genetic loci. A variety of biochemical and immunological techniques have proved useful for detecting genetic polymorphism ( 3, 4). Emphasis in mouse genetics has shifted away from the study of mutants to the study of genetic polymorphisms. There are several reasons why it is desirable to locate these polymorphic genes in the linkage map of the mouse. Traditional methods of linkage testing are slow and uncertain of yielding positive results. A systematic approach is clearly desirable. Recombinant inbred strains represent such an approach.

Recombinant inbred (RI) strains are derived by systematic inbreeding beginning with the F2 generation of the cross of two preexisting inbred (progenitor) strains ( 5). Multiple independent strains are derived without selection. Once inbred, such a set of RI strains can be thought of as a stable segregant population. Unlinked genes are randomized in the F2 generation and are therefore equally likely to be fixed in parental or recombinant phases. Linked genes will tend to become fixed in the same (parental) combinations as they entered the cross. Thus inbreeding preserves part of the linkage disequilibrium generated when two inbred strains are crossed. Once inbred, the RI strains are typed with respect to the numerous genetic differences that distinguish the progenitor strains. Each locus has a particular pattern of inheritance called the strain distribution pattern (SDP). Comparisons are made between different SDPs; a significant excess of parental genotypes, with respect to two SDPs, signals the possibility of genetic linkage. The enormous advantage of this approach is that the data are cumulative. Each RI strain needs to be typed only once for a particular locus. The discoverer of a new variant needs only to type the RI strains for that particular locus. If there is no apparent linkage with any of the available markers, the choice is made to either continue linkage testing by traditional crosses, or wait and hope that as more markers are added to the system that linkage will be revealed. The RI results may exclude linkage to certain chromosomes or parts of chromosomes, thus narrowing further linkage testing.

The chief limitation of the method is that it is only useful for mapping genes that differ in the progenitor strains. If several different sets of RI strains are available, then most polymorphisms will segregate in one or more sets. However, this is no help in mapping new mutations. Another limitation is the poor reproduction encountered in some RI strains.

To quantitate the use of RI strains for linkage analysis, one must relate the probability of fixing a recombinant genotype in an RI strain (R) as a function of the recombination frequency (r) in a single meiosis. This relationship was derived by Haldane and Waddington ( 6). For the case of brother-sister inbreeding, R = 4r/1+6r. (It is of interest that if RI strains are derived by parent-offspring inbreeding R = 3r/1+4r; for selfing, R = 2r/1+2r.) Note that a r approaches zero, R approaches 4r. This can be interpreted to mean that in the development of an RI strain prior to fixation of one allele, it will have been transmitted through a heterozygote four times on the average, each occasion representing an opportunity for recombination with a neighboring gene. Another deduction we can make is that in RI strains we can expect 0.04 crossovers per centimorgan. Thus a chromosome 100 cM in length would have, on the average, four exchanges. Thus in effect, RI strains "expand" the map four-fold. This is an advantage if one is looking for rare recombinants, but a disadvantage when the objective is linkage detection.

By the principle of inverse estimation we can obtain an estimate of r, r-hat = R-hat/4-6R-hat where R-hat is the ratio of recombinant strains relative to the total number or RI strains (n). The estimated variance of r-hat is given by r(1+2r)(1+6r)2/4n ( 7). We can use the reciprocal of the ratio of the variance of r-hat from RI data to the variance of r-hat from an equal number of backcross mice, 4(1-r)/(1+2r)(1+6r)2, to compare the relative efficiency of the two methods per independent marker. From Figure 1 we see that RI strains are more efficient up to r = 0.125, but rapidly become less efficient for greater recombination values. Such a comparison does not reflect the inherent advantage of RI strains, that the data are cumulative permitting the incorporation of more markers, nor the great saving in effort afforded because it is necessary to test only for the new locus. Of course it is relatively easy to increase the number of backcross mice, but the costs may rise if the locus of interest is difficult to type or if many markers are to be followed.

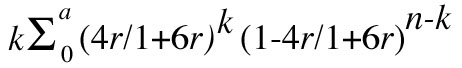

If no recombinants between two loci are detected among n RI strains, the upper confidence limit of r is estimated by solving the following equation for r:

I have attempted to quantify the power of RI strains for linkage detection through the use of Haldane's concept of the radius swept (

8). The statistical power of a method is defined as the probability of rejecting the null hypothesis when it is false. (Note that this is defined to equal 1 - β,

where β is the probability of failing to reject the null hypothesis when it is false. The following calculations are based on adopting a significance level (α) of 0.01.

Having chosen a significance level, we can calculate from the binomial distribution the maximum number of permissible recombinants, such that the null hypothesis of no linkage

would be rejected for a given number of RI strains (

Table 1).

Thus with seven RI strains we would pursue linkages only if no recombinant were observed. With 11 RI strains we would use one recombinant as the

cut-off point, etc. The power function, 1 - β, is equal to

We can use the distance swept (dn) by a single locus in n RI strains to estimate the probability (P) of detecting linkage between a new locus and one or more of m markers randomly distributed over a genome with total length D; P = 1 - (1- [dn/D])m. This neglects the fact that markers near the ends of chromosomes sweep distances less than dn. The total length of the mouse genome has been estimated to be 1600 cM ( 9, 10). Table 2 shows the value of P for different combinations of n and m. It should be noted that dn/D is the a priori probability of detecting linkage between any two loci, assuming a random distribution of loci throughout the map. When n is seven, this ratio is only 0.0058, while the probability of getting a false lead is (1/2)7 or 0.0078. This means that if only seven RI strains are available, and if one only pursues perfect matches, that 57% of these would be expected to be false. Even with larger sets of RI strains a fair proportion of significant matches are expected to be false positives. We can see from Table 2 that with 25 RI strains, 200 markers are required to be 95% confident of detecting linkage of a new marker.

If the polymorphic loci that distinguish the progenitor strains are clustered, then the likelihood of detecting linkage will be increased for small values of m, but clustering may retard the approach to saturation as m becomes large. In practice, some degree of clustering is to be expected, For example, all immunoglobulin structural genes are expected to fall into three clusters coding for heavy, kappa, and lambda chains. Localization of chiasmata would also enhance clustering ( 11). Insofar as the progenitor strains are related, certain chromosomal segments may be identical by descent, just as pairs of RI strains will share blocks of genes with each other. Major evolutionary changes in the karyotype of the species, such as the fixation of reciprocal translocations, may result in the loss of polymorphisms in the chromosomes involved. Certain chromosomal regions may be deficient in genes and comprise redundant DNA of unknown function.

In addition to detecting linkage and estimating recombination frequency, it is desirable to determine the linear order of genes on the chromosomes. The ease with which multiple markers can be scored in RI strains lends itself to gene ordering. In conventional mapping, once linkage has been detected, one or more additional crosses are often needed to define the correct gene order with respect to the new linkage and neighboring loci. In the case of polymorphic loci which often require specialized techniques for typing, it may not be practical for a single investigator to carry out the tests needed to determine gene order. RI strains offer the possibility of ordering such loci. Gene ordering depends on the fact that double crossovers are relatively rare compared to single crossovers. Interference is defined as a deficiency of double crossovers relative to the product of the frequency of single crossovers in adjacent intervals. Since exchange points along a chromosome fixed in an RI strain may have occurred in different individuals during the development of the strain, interference is likely to be weak. I have carried out preliminary computer simulations of RI strain formation to investigate the distribution of crossover points along a chromosome. One model was of a chromosome 50 cM in length, using the mapping function r = d, 0 < d < 0.5. In other words, the probability of a crossover in any meiosis was 0.5, and the location of the crossover point was random. No multiple crossovers were allowed. Therefore, interference was complete. The number of exchanges/10 cM segment of the chromosome was tabulated in several hundred runs. The mean number of exchanges agreed well with the expectation (0.4). The number of segments with 0, 1, 2, 3, ... exchanges agreed remarkably well with a Poisson distribution with mean of 0.4, implying that the complete interference model in meiosis generates RI chromosomes that resemble chromosomes that would be generated in a situation with no interference. This model, if valid, greatly simplifies prediction of the distribution of crossover points. Thus we would predict that exchange points would be randomly distributed along the chromosome. This means that, although the likelihood of two exchange points occurring between two closely linked genes is necessarily small, occasionally it will happen. Therefore, we should expect to occasionally obtain three point data that are ambiguous regarding gene order or, more rarely, the data may be misleading in regard to gene order. A corollary would be that one is not assured that because an RI strain has become fixed for two closely linked markers from the same progenitor that the entire segment between those markers was inherited intact.

Although seven is near the minimum number of RI strains sufficient for detecting linkage, it is worth emphasizing that even a single RI strain can be very valuable. A single recombinant is sufficient to show that two loci are distinct or to indicate gene order. Thus RI strain data may indicate gene order of loci that were shown to be linked by other means. Therefore, existing miscellaneous RI strains should be maintained and characterized genetically.

Bailey ( 5) was the first to develop RI strains of mice. From the cross of BALB/cBy and C57BL/6By he derived seven RI strains. Although seven is near the minimal number of RI strains sufficient to detect linkage, a perfect match or near match is a good enough hint to encourage further testing. Using these CXB RI strains, Bailey and his collaborators have found approximately 20 linkages ( 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19).

I began making several sets of RI strains shortly after arriving at The Jackson Laboratory in 1969. The status of these strains is given in Table 3. Most of these strains have now attained a high degree of inbreeding such that heterozygosity is encountered only rarely. The BXD RI strains are outstanding in regard to the number of strains (twenty-four), the number of loci at which they have been typed (sixty-five), and the number of chromosomes with at least one marker (fourteen). All four of these sets have been useful for gene mapping and a total of 20 linkages have been detected. Some of these are listed in Table 4. There are presently 32 loci for which there are SDPs but no evidence for any linkage. Thus the success rate appears to be about 40%. The power of RI strains for gene ordering is illustrated by the example of seven markers distributed over approximately 40 cM of chromosome 9 in the BXD RI strains ( 20, 21, and unpublished observations). A minimum of 34 exchange points are identified by these seven loci. Each exchange point potentially defines the location of yet-to-be discovered loci in this region. I am also in the process of developing some additional miscellaneous RI strains. These are, in general, for special purposes, few in number, incompletely inbred, and not extensively tested as yet. A number of other workers outside The Jackson Laboratory are presently developing RI strains. Although it seems likely that a point of diminishing returns will be reached regarding additional sets of RI strains, it is too soon to know if it has yet been reached.

The number of loci typed in the RI strains has been increasing by about ten per year for the past several years. The technique of isoelectric focusing, either alone or combined with conventional electrophoresis, promises to reveal numerous protein polymorphisms not seen with electrophoresis alone. The application of these techniques to RI strains is expected to result in a quantum jump in the number of loci typed. Recent developments in DNA chemistry and the ability to clone may make it possible to recognize strain differences at the DNA level. Presumably, when more workers become aware of RI strains and their potential usefulness, they will avail themselves of this tool. Therefore I am optimistic that in the next few years we will see the RI method come into its own in mouse genetics.

1These studies were supported in part by contract NO1 CP33255 within the Virus Cancer Program of the National Cancer Institute, and by NIH research grant GM 18684 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. The Jackson Laboratory is fully accredited by the American Association of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC).

1. Lewontin, R.C., and Hubby, J.L. (1966). Genetics 54: 595.

See also

PubMed.

2. Harris, H. (1966). Proc. Roy. Soc. Lond. 164: 298.

See also

PubMed.

3. Roderick, T.H., Ruddle, F.H., Chapman, V.M., and Shows, T.B. (1971). Biochem. Genet. 5: 457.

See also

PubMed.

4. Snell, G.D., and Cherry, M. (1972). In RNA Viruses and Host Genome in Oncogenesis (P. Emmelot and P. Bentvelzen, eds.). North-Holland, Amsterdam.

5. Bailey, D.W. (1971). Transplantation 11: 325.

See also

MGI.

6. Haldane, J.B.S., and Waddington, C.H. (1931). Genetics 16: 357.

See also

MGI.

8. Haldane, J.B.S. (1956). J. Genet. 54: 327.

9. Carter, T.C. (1955). J. Genet. 53: 21.

10. Searle, A.F., Berry, R.J., and Beechey, C.V. (1970) Mutat. Res. 9: 137.

See also

PubMed.

11. Lyon, M.F. (1977). Genet. Res. 28: 291.

12. Bailey, D.W., and Hoste, J. (1971). Transplantation 11: 404.

See also

PubMed.

13. Merryman, C.F., Maurer, P.H., and Bailey, D.W. (1972). J. Immunol. 108: 397.

See also

PubMed.

14. Blomberg, B., Geckeler, W., and Weigert, M. (1972). Science 177: 178.

See also

MGI.

15. Oliverio, A., Eleftheriou, B.E., and Bailey, D.W. (1973). Physiol. Behav. 10: 893.

See also

MGI.

16. Eleftheriou, B.E., and Kristal, M. (1974). J. Reprod. Fertil. 38: 41.

See also

MGI.

17. Wikstrand, C.J., Haughton, G., and Bailey, D.W. (1974). Cell. Immunol. 10: 238.

See also

PubMed.

18. DeMaeyer, E., DeMaeyer-Guinard, J., and Bailey, D.W. (1975). Immunogenet. 1: 438.

19. Bailey, D.W. Personal communication.

20. Womack, J., Lynes, M.A., and Taylor, B.A. (1974). Biochem. Genet. 13: 511.

See also

PubMed.

21. Meisler, M.H. (1976). Biochem. Genet. 14: 921.

See also

MGI.

22. Taylor, B.A., and Meier, H. (1975). Genetical Res. 26: 307.

See also

PubMed.

23. Festenstein, H., Bishop, C., and Taylor, B.A. (1977). Immunogenet. 5: 357.

See also

MGI.

24. Wilson, C., Wilson, J., and Taylor, B.A. (1978). Mouse News Letter 58: 49.

25. Watson, J., Riblet, R., and Taylor, B.A. (1977). J. Immunol. 118: 2088.

See also

MGI.

26. Watson, J., Kelly, K., Largen, M., and Taylor, B.A. (1978). J. Immunol. 120: 422.

See also

MGI.

27. Taylor, B.A., Bedigian, H.G., and Meier, H. (1977). J. Virol. 23: 106.

See also

MGI.

28. Taylor, B.A., and Shen, F.W. (1977). Immunogenet. 4: 597.

See also

MGI.

29. Claflin, J.L., Taylor, B.A., Cherry, M., and Cubberley, M. (1978). Immunogenet. (accepted).

30. Taylor, B.A., and Wood, A.W. (1976). Mouse News Letter 54: 41.

31. Skow, L., and Taylor, B.A. (1977). Mouse News Letter 57: 19.

See also

MGI.

32. Stern, R.H., Russell, E.S., and Taylor, B.A. (1976). Biochem. Genet. 14: 373.

See also

MGI.

33. Day, C., and Nesbitt, M. (1977). Mouse News Letter 57: 10.

See also

MGI.

34. Womack, J.E., Taylor, B.A., and Barton, J.E. (1978). Biochem. Genet. 16: 1107.

See also

MGI.

35. Mishkin, J.D., Taylor, B.A., and Mellman, W.J. (1976). Biochem. Genet. 14: 635.

See also

MGI.

36. Cumming, R.B., Walton, M.V., Fuscoe, J.C., Taylor, B.A., Womack, J.E., and Gaertner, F.H. (1978). Biochem. Genet. (submitted).

37. Taylor, B.A., Bailey, D.W., Cherry, M., Riblet, R., and Weigert, M. (1975). Nature 256: 644.

See also

MGI.